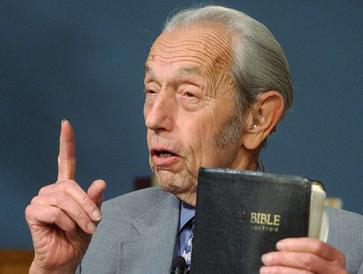

I met Dr. William Young in November of 1992. Our congregation in Des Moines had petitioned the Presbyterian Reformed Church to be taken into their denomination. He had been part of a committee sent by the Presbytery of the Presbyterian Reformed Church to meet with our congregation and examine the church officers. I walked into the room where we were meeting and he was already there seated at a table. He was unpretentious and, as always, a bit disheveled. He introduced himself simply as “William Young”.

Over the course of the day, we discussed a lot of things: Who we were, who the Presbyterian Reformed Church was, and, of course, during our examination they asked us a lot of questions. As we got to know a bit more about where the other was coming from, we also had the occasional small debate as well. I found myself in a rather protracted debate with Dr. Young about the Received Text and the meaning of providential preservation in the Westminster Confession. I had absolutely no idea who I was dealing with at the time, but in retrospect I was like a kid with a pea-shooter going up against a Howitzer.

He was incredibly kind and patient with me, and didn’t destroy me with his intellect and his vast knowledge, which he certainly could have done.

That evening we stopped at a tobacco shop before heading back to my home, where we stayed up very late sitting by the fireplace smoking cigars and talking. I learned that if you asked the old boy a question you’d better be prepared to listen to the answer for the next forty-five minutes. That first night, I learned about the Clark-Van Til controversy that Dr. Young had found himself in the middle of, I heard about the beginnings of the Rhode Island congregation of the Presbyterian Reformed Church, and Herman Dooyeweerd’s “cigar shop” analogy. He also spoke at some length about his relationship with Dr. Clark, the discussions they had, and how, on one occasion when they were discussing quantum mechanics, Dr. Clark replied to Dr. Young, “I am silenced, but unconvinced.” By this time, I had an inkling of who I was dealing with: This was the most brilliant man I was ever to meet. And one of the most eccentric as well.

That first night I found myself wiping a pile of cigar ash off his necktie before it caught on fire. It wouldn’t be the last time for that sort of thing. He was just oblivious to stuff like that.

The next evening, several of us were gathered together at our home, and Dr. Young was once again seated near the fireplace. I can’t recall exactly how it came about, but he ended up with my son Jonathan on his lap, and Dr. Young was reading Vergilius Ferm’s Pictorial History of Protestantism to him. Jonathan sat on the old man’s lap for most of the evening listening to him tell about Luther and Zwingli at Marburg and such like. It wasn’t until many years later that I realized what a special thing that was, and I hope Jonathan remembers the night he was tutored in Protestant church history by a man who possessed one of the greatest minds in all of Reformed Christianity.

By the time the weekend was over, I knew I had definitely made a fast friend. I admired him immensely and really got a kick out of him. I looked forward to seeing him again. I think he genuinely liked me too. I think he generally liked anybody that he could go have a smoke with, and I guess I fit that bill.

So, for the next twenty years or so we’d see one another on a fairly regular basis. We’d be at a Presbytery meeting together or we’d see one another on one of my many trips to Rhode Island where he was pastor of the Presbyterian Reformed Church congregation there. Between sessions of Presbytery meetings or between services at church, Dr. Young would almost always shuffle over to wherever I was and ask if I was interested in going outside to join him and Vinnie Gebhart and whoever else for a smoke. Some of my fondest memories of Dr. Young involved conversations we had during the enjoyment of a couple of good cigars. We had a lot of laughs, too. He was always happy with a cigar in his hand.

Over the years he and I managed to tick one another off at Presbytery meetings, but the irritation never lasted long between us. We’d be out having a laugh and a smoke afterwards, and that would be the end of that.

He certainly had an opinion on lots of things, but frequently he could be rather puzzling as to just where he really stood. On the one hand, he was always ready to tell you that he didn’t think much of Geerhardus Vos’ biblical theology or Abraham Kuyper’s presumptive regeneration, but, on the other hand, he would make these cryptic statements about other subjects that just left you guessing and scratching your head. I think he liked it that way.

Sometimes he could be incredibly funny. You more or less had to know him a bit to understand that.

One Lord’s Day after a Presbytery meeting in Portland, OR, several of us were on an afternoon walk near the base of Mt. Hood where one of our church families lived. A couple of us were holding on to Dr. Young’s arms as we walked up the hill, and he was asked how he was doing and if the pace was okay. He was, after all, in his early eighties at the time. “Oh,” he said, “this is child’s play.” The way he said it made it sound as if he was incredulous that we would even ask such a thing, and we all broke into laughter as soon as he said it.

But he wasn’t done: “I admit I’m not the man I was when I took my alpenstock and traversed the glacier…” He went on to tell us about how he and his companion misread the signs and took a trail that was extremely dangerous, and that he nearly fell into a crevasse. From there he went on from one story to another going back some sixty years. By the time he had described to us his struggles with Phys-Ed classes at Columbia, I had tears rolling down my face and my sides ached from laughing so hard. We were all listening and laughing, and the old boy knew he was working us like a stand up comedian. He was loving it.

He would occasionally make a face to show how absurd he thought something was, and it involved sticking his tongue out, closing his eyes, and shaking his head rather violently. It was priceless to see that.

Traveling with Dr. Young must have always been a memorable event. On one occasion, Dr. Young was traveling with Vinnie and John Humphrey via airplane to a Presbytery meeting somewhere. One of them must have asked him a question, and the next thing they knew, there was Dr. Young, loudly lecturing on the philosophical history of the nature of perception and Einstein’s theory of relativity. It had to be quite a treat for the rest of the passengers, who Dr. Young was, no doubt, quite unconscious of.

The last several years were difficult for him, as his health was increasingly failing, and he was in and out of various medical facilities, including nursing homes that he absolutely abhorred. Through the efforts of Michael Ives, he eventually was able to receive around the clock in-home care, but in the beginning he was stuck (imprisoned was how he viewed it) in a nursing home. On one of my visits to Rhode Island during this time, he asked to speak to me privately. I went to his room convinced he was going to give me a list of grievances about his situation, but I was completely wrong. He simply wanted to make an inquiry about the spiritual well being of my two sons. I was deeply touched by his concern, especially knowing how stressed and unhappy he was at the time.

I owe the man a great deal. It was through hearing his lectures and reading his articles that I gained an understanding and appreciation of experimental religion. He pointed me to writers like Archibald Alexander and Thomas Boston. And for the first time, I was able to reconcile my Calvinism with the warm Evangelicalism of my youth.

I’m grateful to him for other things as well. Some of our dearest friends came to know Christ under his ministry, and his involvement in the denomination I love has left an imprint that I trust the rest of us will always take notice of.

It’s been awhile now since I last had a smoke and a laugh with my old friend. I miss those times. In my mind’s eye I see him pretty clearly, however: It’s Winter, and he’s wearing his heavy wool overcoat and his coonskin hat, and, just like I did the first time I saw him wearing it,

I chuckle.